Anni Säär

Lots of people change their place of residence to move in with their spouse, or make great changes due to economic reasons, or to accept a better job offer. However, there are people, who are leaving their country of origin not by choice, but they are forced to leave because their life and/or health (and often also that of their family) is at stake. Refugees need special protection precisely because they have not chosen this fate for themselves. 1997 can be considered the beginning of Estonia’s refugee policy. That was the year the first act concerning refugee law – the Refugees Act[1] – was adopted, as well as the year Estonia acceded to the Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and the 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees.[2] By now the Refugees Act is null and void as it has been replaced by the Act on Granting International Protection to Aliens, which was passed in 2005.[3] Therefore, it can be said that Estonian refugee law is still extremely young compared to law in other areas and that is why it is natural that there is room for improvement. Refugee law has been integrated into national legislation, but the state must also consider, as well as apply international legislation, which it is bound by.

The greatest development in the field in 2013 was undoubtedly the coming into force of the Act on Granting International Protection to Aliens and the act amending other relevant acts on 1 October 2013. The development on the European Union level that is worth mentioning is the adoption of last parts of the Common European Asylum System in 2013, some of which came into force in the beginning of 2014, but the majority of which must be transposed into national law by June of 2015.

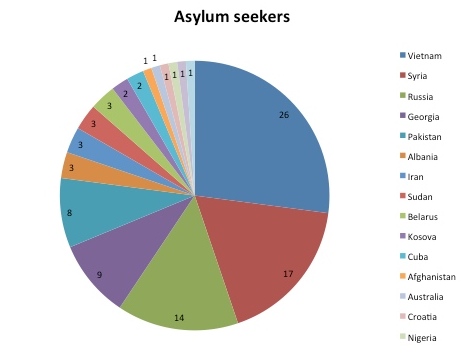

97 applications for asylum were submitted in 2013, which is 20 more than the previous year.[4] The number of applications for asylum has been on the rise in Estonia year on year, yet the number of persons enjoying international protection has decreased. If in 2012 the number of applications granted was 13 out of the 77 (refugee status was acquired by 8 persons and subsidiary protection was given to 5 persons), in 2013 just 7 applications were granted.[5]In 2013 three persons were given residence permit via family reunification, in 2012 it had been given to ten persons.[6] The largest number of applications in 2013 was submitted by Vietnamese citizens – 26 applications.[7]

Political and institutional developments

On 12 March 2013 the advisers to the Chancellor of Justice and the Police and Border Guard Board carried out a verification visit to the detention centre. Pursuant to the verification visit the Chancellor of Justice passed on his recommendations to the Police and Border Guard Board on 3 June 2013 to be followed, and on 8 January 2014 published a memorandum,[8] which had been drafted as a result of the subsequent verification visit made on 29 November 2013. The memorandum points out that the practice of using handcuffs has been significantly changed after the previous verification visit (handcuffs were used on few occasions in case of, for example, visiting a dentist), but the reasons given for using handcuffs are still vague and not related to factual circumstances describing the detention. The Chancellor of Justice also pointed out the fact that cultural particularities should be considered more in regards to catering, especially considering the fact that the expulsion centre has been reorganised into a detention centre for aliens and considering these particularities is becoming increasingly important. The Chancellor of Justice also turned his special attention to problems concerning psychological counselling – persons who did not speak Estonian, Russian or English did not have access to psychological counselling. The European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) has drawn attention to the fact that persons staying at such detention centres are in a particularly vulnerable situation, as their mental health may have been influenced by traumatic experience that has taken place in the past. They are also unaware of their future and the duration of their detention and are outside their habitual personal and cultural environment. All these circumstances may cause deterioration of the person’s mental health and facilitate depression, anxiety and bring on posttraumatic stress or flaring up of relevant symptoms.[9] As the asylum seekers have generally fallen victim to persecution and abuse they are in an extremely vulnerable situations in detention centres where their psychological problems are not addressed sufficiently, moreover, the detention is highly likely to increase their problems. The Chancellor of Justice also recognised the Police and Border Guard Board for taking steps to diversify the options for passing the free time for persons at the detention centre (sports, language learning, handicraft).

According to the law the Ministry of Social Affairs or its agency should organise the housing of persons enjoying international protection into local self-government within four months of the day the residence permit was given. If the non-governmental organisations had previously pointed to the fact that there were apparent problems with allocation of housing, the current practice shows that the accommodation centre does organise the accommodation for persons enjoying international protection in local governments within the time prescribed by law.

A positive change worth noting is also the fact that the accommodation centre of asylum seekers moved from Illuka rural municipality (Jaama village) to Väike-Maarja rural municipality (Vao village), where the access to necessary services is much better in January of 2014.

Legislative developments

One of the greatest developments of 2013 is the coming into force of the Act on Granting International Protection to Aliens and the act amending relevant acts on 1 October 2013.

Before, the detention of asylum seekers was stated in § 33(1) of the act: “The applicant, who submitted his application while staying at the expulsion centre, prison or a house of detention or in the course of the expulsion, will not be placed in the preliminary reception centre, but he must stay at the expulsion centre, prison or the house of detention until the end of asylum proceedings. If an alien who has submitted an application while staying in prison or a house of detention will be released from prison or a house of detention and referred to the reception centre.” The provision was worded in an imperative manner and in practice meant that if the person sought asylum in an expulsion centre (the current detention centre) he had to remain there until the end of proceedings. If he did not receive the refugee status and a subsidiary protection the person also had to stay at the expulsion centre during the court proceedings.

The basis for detention is stated in § 361 of the amended act. According to the Act on Granting International Protection to Aliens § 361(1) an asylum seeker may be detained if the efficient application of surveillance measures stated in this Act is impossible. The detention shall be in accordance with the principle of proportionality and upon detention the essential circumstances related to the asylum seeker shall be taken account of in every single case. The explanatory memorandum to the second reading of the draft act amending the Act on Granting International Protection to Aliens and other relevant acts (354 SE II) has explained about the application of § 361 that detention is possible in the presence of a strictly worded provision if the surveillance measures cannot be efficiently applied, also the purpose, necessity and proportionality of the detention must be considered, and in every single case the circumstances related to it must be considered (for example, vulnerability), detention must also be unavoidably necessary – the asylum proceedings would not be possible in any other way. Therefore, detention must truly be the last method for guaranteeing asylum proceedings.

Unaccompanied refugee minors, considering their mental and often also physical condition, are an easy target to human traffickers. Articles 34-37 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child state that the member states have the duty to protect children from all forms of exploitation that harm the wellbeing of the child (including sexual exploitation) and abuse, and the states have the obligation to take measures to avoid it. State of Estonia has solved the situation by sending unaccompanied minors to shelters or to children’s homes.

Court practice

Since the field of refugees and asylum seekers was not legally regulated in Estonia before 1997 and over the years there have been fewer than 500 asylum applications in Estonia (since 1997), there is insufficient court practice regarding asylum application.

Given the fact that the amendment to the act regarding detention of asylum seekers came into force on 1 October 2013, there is already some court practice. Unfortunately the court practice varies and legal clarity is not guaranteed. Refugees, who often have to flee from their country, can rarely follow the legal requirements for entering the receiving state (having a visa/passport).

It is worth mentioning that the court practice of Tallinn Administrative Court and Tartu Administrative Court and the assessment of unavoidable need upon placing the asylum seekers in the detention centres vary.

According to the practice of Tallinn Administrative Court[10] the following prerequisites have to be fulfilled in order to detain the asylum seeker at the detention centre:

1) efficient application of surveillance measures stated in the Act on Granting International Protection to Aliens is impossible;

2) detention shall be in accordance with the principle of proportionality;

3) the essential circumstances related to the asylum seeker shall be taken account of in every single case;

4) detention is unavoidably necessary.

In addition to considering these four points upon placing the asylum seekers at detention centres the court has found that the person’s cultural background and the circumstances for arriving in Estonia (Syria’s civil war) must also be considered.

The majority of asylum seekers who are placed in detention centres by the permission of Tartu Administrative Court, have arrived in Estonia by crossing the border illegally. As can be seen by the practice of Tartu Administrative Court, the method of the persons’ entering the state plays a role in their placement at a detention centre, although Article 26 of the 1951 Convention entails the statement of non-penalty, which, according to international legislation on refugees, does not give the state an automatic right to detain the persons even in the case they entered the country without the necessary permits. Tartu Administrative Court has repeatedly claimed, upon assessing the placement of persons in detention centres: “as the person arrived in Republic of Estonia illegally, there is a danger he may escape and it cannot be precluded that his application for an asylum has been submitted in order to avoid an expulsion.” Article 31 (1) of the 1951 convention states the following: “The Contracting States shall not impose penalties, on account of their illegal entry or presence, on refugees who, coming directly from a territory where their life or freedom was threatened /—/provided they present themselves without delay to the authorities and show good cause for their illegal entry or presence.” The court practice has also supported this, for example in the United Kingdom judgment of R v. Uxbridge Magistrates Court and Another, Ex parte Adimi the court stated that the protection stated in Article 31 (1) of the 1951 Convention is applied to refugees, asylum seekers and to those who use false documents or enter the country secretly.[11] It can be concluded that the session for assessing whether to place a person in a detention centre should assess whether effective application of surveillance measures is possible, whether detention is unavoidably necessary, whether the principle of proportionality has been followed, and consider essential circumstances related to the asylum seeker. It must be pointed out that it is not proportionate to place a person who has identity documents, which are clearly not false, in the detention centre for the purpose of identifying the person.

Public discussions and trends

The biggest public debates arose regarding Estonian Human Rights Centre’s project “Raising Awareness in Society on International Forced Migration”. A lecture series “International forced migration” took place from February to May and was open to students from Tallinn Technical University, University of Tartu and Tallinn University, and was taken part of by over a hundred students. Debates on forced migration took place in online environment of Postimees from January to June. The largest awareness raising campaign on refugees “A postcard from a refugee” in Estonia took place in March of 2013, which reached six million contacts. On the World Refugee Day, June 20th, a special annex on the topic of forced migration was published with Postimees. At the end of the year the Estonian Human Rights Centre and the Estonian Refugee Council organised a charity event in support of refugees, raising money for opening an integration centre for the refugees.

In June the Estonian Human Rights Centre initiated the media debate about border monitoring based on tips that a Syrian citizen had been sent back from the border by Estonian border guards, which resulted in a commonly issued press release by three organisations involved with refugees – the Johannes Mihkelson Centre, the Estonian Human Rights Centre and the Estonian Refugee Council. On an international level the necessity of border monitoring has been emphasised to the Ministry of the Interior by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees as well as the European Council on Refugees and Exiles. Border monitoring would contribute towards the situation where refugees crossing the border illegally are not treated as criminals, and to make the activity at border crossing points more transparent. The UN Refugee Agency has repeatedly stated that refugees should not be treated as criminals and their illegal border crossing should not be punished as they often do not have the legal option for entering a country. Border monitoring would make it possible to guarantee that human rights of refugees – the right to apply for an asylum – are guaranteed. Border monitoring would help decrease the current practice, where asylum seekers with a Russian visa may be handed over to Russia, where their rights may not be protected. It is also interesting that in Latvia, where there is independent border monitoring, in 2012 there were nearly three times as many asylum applications registered as in Estonia.[12]

The change of location of the asylum seekers’ accommodation centre in January of 2014 made communication with them easier and guaranteed a better access to services that they need. The reception conditions and services allotted for asylum seekers (especially for asylum seekers with special needs) and refugees are better than last year, but there are grey areas, which would benefit from a change in legislation or a better application of the existing legislation.

On December 9th, 2013 the International Human Rights Day was celebrated with a charity event at the winter garden of Estonian National Opera in support of refugees. The event was organised by the NGO Estonian Refugee Council, about 150 people were present and about 6000 euros were raised towards repairing the Tartu refugees’ integration centre and for starting its work. Advocacy activities were also continued – a round table for refugee organisations was organised and meetings with ministries (Ministry of the Interior, Ministry of Social Affairs) and other authorities (AS Hoolekandeteenused, Integration and Migration Foundation) took place. The topic of refugees’ right to work has also received attention; Eero Janso also wrote an analysis about it.[13] Legal counselling of asylum seekers and representation by the Estonian Human Right Centre also continued, as did offering of support services by Johannes Mihkelson Centre, which trained more support persons in 2013.

Integration of refugees into the society continues to be problematic. Refugees are often confused with migrants, which refers to society’s ignorance or lack of desire to be informed.

Recommendations

- Estonian Republic should allow border monitoring to take place in order to chart the current situation regarding refugees on the borders.

- Put together informative material to persons enjoying international protection regarding their rights and obligations with the necessary contact information in languages that are spoken most by the asylum seekers.

- Create a proper system, which would help refugees integrate into the society.

- Continue with awareness raising campaigns about refugees, thereby increasing awareness in the society.

- Not to place asylum seekers in detention centres on the presumption that the person will escape as he has entered the country illegally.

[1] Refugees Act. State Gazette I 1997, 19, 306.

[2] Pagulasseisundi konventsiooni ja 31. jaanuari 1967. aasta pagulasseisundi protokolliga ühinemise seadus [The act on acceding to the Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and the 31 January 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees]. State Gazette II 1997, 6, 26.

[3] Act on Granting International Protection to Aliens. State Gazette I 2006, 2, 3; State Gazette I, 09.12.2010, 4.

[4] Einmann, A. Postimees. „Eesti andis mullu varjupaiga seitsmele inimesele“ [Last year Estonia granted asylum to seven persons]. 05.01.2014. Available at: http://www.postimees.ee/2651314/eesti-andis-mullu-varjupaiga-seitsmele-inimesele.

[5] Saharov, J., Anni Säär. Pagulaste ja varjupaigataotlejate olukord [The situation of refugees and asylum seekers]. Available at: https://humanrights/inimoiguste-aruanne-2/inimoigused-eestis-2012/pagulaste-ja-varjupaigataotlejate-olukord/.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Einmann, A, op. cit.

[8] Chancellor of Justice’s memorandum 08.01.2014 7-7/131436/1400088. Available at: http://oiguskantsler.ee/sites/default/files/field_document2/jarelkontrollkaigu_kokkuvote_ppa_valismaalaste_kinnipidamiskeskus.pdf.

[9] Chancellor of Justice’s memorandum 08.01.2014 7-7/131436/1400088. Page 6. Arv Available at: http://oiguskantsler.ee/sites/default/files/field_document2/jarelkontrollkaigu_kokkuvote_ppa_valismaalaste_kinnipidamiskeskus.pdf. Original text in English: 9 19th General Report of the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT). 1 August 2008-31 July 2009. P 90. Page 41.

[10] Tallinn Administrative Court administrative matter no. 3-13-2245, nr 3-13-70068, no. 3-13-70069, no. 3-13-70070 and no. 3-13-70071.

[11] R v. Uxbridge Magistrates Court and Another, Ex parte Adimi, United Kingdom High Court (England and Wales). 29.07.1999. Available at: http://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b6b41c.html.

[12] Estonian Human Rights Centre: Varjupaigataotlejad tuleb ära kuulata [The asylum seekers must be heard]. 20.06.2013. Available at: https://humanrights/2013/06/eesti-inimoiguste-keskus-varjupaigataotlejad-tuleb-ara-kuulata/.

[13] „Kuidas elada, kui ei ole õigust töötada? Seisukohavõtt varjupaigataotlejatele töötamise õiguse andmise kohta“ [How do you live if you don’t have the right to work? An opinion on giving asylum seekers the right to work.]. Available at: http://www.pagulasabi.ee/sites/default/files/public/eesti_pagulasabi_-_varjupaigataotlejate_tootamise_oiguse_analuus.pdf.